Hugh Matthews Survived Civil War POW Camp, Returning to Work & Raise His Family

Throughout the pages of the recently-released historical novel The Penny by Michigan author Stewert James, readers find intertwined storylines that bring generations of families and friends together during often difficult times. One of the more compelling stories, one that warrants a more in-depth look, is Hugh Matthews – James’ great-great-grandfather.

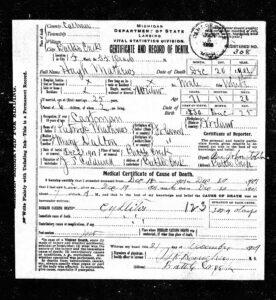

Hugh Matthews (sometimes written as Mathews) was born in the county of West Meade, Ireland to Patrick and Margaret McVenna (also printed McKanna and/or McCanna, although some sources, like his death certificate, erroneously list his mother as Mary Dalton (which was actually the name of his wife or Mary Dutton, a woman unknown to descendants)). He was the oldest of four children (James, born in 1831; Anna, born around 1834; and Bryan, born in 1838). While his death notice notes his date of birth was December 25, 1830, a baptism record from Ireland is dated February 27, 1829—a full 10 months earlier.

Between the ages of 18 and 20, Hugh immigrated to the United States aboard the Roscins, arriving January 1, 1849, according to boat records at StatueOfLiberty.org. First residing in Vermont, Hugh ultimately moving to the southern Michigan town of Battle Creek in Calhoun County. There, in 1855, he married Irish-born Mary (Whalen) Dalton (1828-1901)—“a very estimable lady” according to one newspaper article—and the couple had six children: Edward P (1857-1929), Margaret “Maggie” Elizabeth (1858-1931), Catherine “Katie” (1860-1871), Mary (1862-1871), Eleanor “Nellie” (1866-1871) and John (1868-1870). Only two of their children lived into adulthood: Edward, who would go on to marry Mary A. (Cassady or Cassidy) around 1884, and Margaret, who would become Mrs. John Tobin (the branch of the family tree from which James descends).

Over the next several years, Hugh would live and work in Battle Creek, most notably as a farmer. In the early 1860s, the country was in turmoil and the now thirty-something Hugh joined fellow Michiganders in serving with the Union forces.

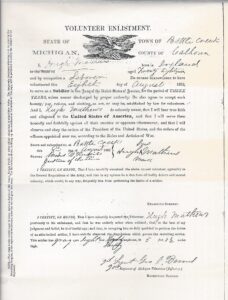

Many official records from the Civil War have been lost to time, dates are often misprinted, details inadvertently omitted and various sources provide contradictory information. According to his Volunteer Enlistment documentation, he committed to a period of three years when he signed this document (with an X) on August 8, 1862 and thus began his career with Company C 20th Michigan Infantry which formally organized in Jackson, Michigan between August 15 and 19 of that year.

According to the “Historical Sketch & Roster of the 20th Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment” online at ResearchOnline.net, this unit was led by Colonel Adolphus Wesley Williams. They left for Washington, D.C., September 1 and thus began Hugh’s stint as a Civil War soldier.

The unit’s first noted engagement was from September 22 to October 6 at Sharpsburg, MD, followed by the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, December 13, 1862; Horse Show Bend, Kentucky, May 10, 1863; Vicksburg, Mississippi, July 4, 1863; Blue Springs, Tennessee, October 9, 1863; Campbell’s Station, Tennessee, November 16, 1863; and Siege of Knoxville, Tennessee, November 17 to December 4, 1863, among many others. Hugh’s involvement on the front line came to an abrupt halt on June 2, 1864, during the Battle of Cold Harbor, approximately 10 miles northeast of Richmond, Virginia.

According to The American Battlefield Trust website (Battlefields.org), this “dramatic and decisive” 13-day engagement (May 31 to June 12) is regarded as one of the war’s bloodiest battles with 18,000 soldiers killed, wounded or captured from both sides. History.com notes that “out of some 108,000 troops, the Union suffered 13,000 casualties, while the Confederates suffered 2,500 casualties out of 62,000 troops.”

In the Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, the 1885 autobiography of his life, Grant said “I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. … No advantage whatever was gained to compensate the heavy loss we sustained.”

While the Battle of Cold Harbor was a tactical success for the Confederate, it was said to be a strategic turning point in the Civil War. There was little chance after that the south could gain victory in the war.

Just 20 minutes into Grant’s debacle of the charge at Cold Harbor, in the wee hours of the morning, Hugh was taken prisoner and initially housed Libby Prison in the Confederate capital of Richmond, VA. It was primarily used for officers, although many enlisted men would come through Libby Prison to be registered as POWs before being transferred elsewhere. It was one of the many POW camps which housed Union soldiers in deplorable and often inhumane conditions. Thousands of prisoners were confined in spaces much too small for their numbers and many suffered from disease and malnutrition, leading to a high mortality rate.

Libby is regarded as second only in notoriety to Andersonville in Georgia for its horrific conditions. After a short stint at Libby, Hugh was transferred out along with countless other POWs to this barbaric facility.

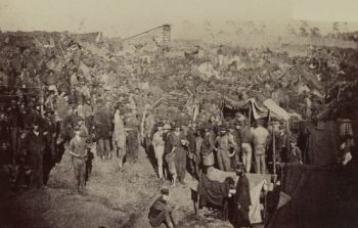

Andersonville, or Camp Sumter as it was officially known, was one of the largest Confederate military prisons in operation during the Civil War and at its peak was more than eight times over-capacity. Established in 1864 to supposedly ease overcrowding of other prison camps, the 26.5-acre compound located deep in the bowels of Georgia was only meant to hold 10,000 prisoners. During its 14-months of operation, Anderson housed well over 52,000 men.

“The prisoners slept on the bare ground – there were no tents, huts, barracks or shelters,” notes James, who visited the site with his wife, about five years ago. “Each Union soldier, using shirts, coats or rags, had to fashion a swale of dirt into a home for as many months as he could survive. There was a creek that was used for water, washing and toileting. Some men would dig with their bare hands to find springs, adding to the water supply, only to have them muddied and vilified as more men tried to use them.”

Battlefields.org notes “There were simply too many prisoners and not enough food, clothing, medicine, or tents to go around. Limited rations, consisting of cornmeal, beef and/or bacon, resulted in extreme Vitamin-C deficiencies which often times led to deadly cases of scurvy…in addition…many prisoners endured intense bouts of dysentery which further weakened their frail bodies. Prisoners at Andersonville also made matters worse for themselves by relieving themselves where they gathered their drinking water, resulting in widespread outbreaks of disease, and by forming into gangs for the purpose of beating or murdering weaker men for food, supplies and booty.”

The conditions at Andersonville and Libby were among the most horrific, but many camps on both sides off the war operated in similar fashion. Without question, Andersonville is the Civil War’s most infamous and deadly prison camp. In all, 13,000 prisoners died there and were subsequently buried in mass graves on land adjacent to the prison.

The Andersonville cemetery was established as a National Cemetery on August 17, 1865 and today is the final resting place for not only those who died at Camp Sumter but also for veterans from many conflicts of wars, with approximately 19,000 interments currently. The grounds also serve as a National Historic Site and is home to the National Prisoner of War Museum, which was established in 1998.

In December 2018, the American Battlefield Trust helped preserve six crucial acres at the Cold Harbor battlefield that is contiguous with the National Park Service property there.

The 20th Regiment – which was made up of about a dozen companies from southern Michigan – lost 13 officers and 111 enlisted men who were either killed in action or mortally wounded, while three officers and 175 enlisted men died of disease during the course of their service in the Civil War. In all, a total of 302 fatalities were reported out of just over 1700 men on the roster.

Hugh survived his combined 11 months of hell inside the confines of Libby and Andersonville, although the wear on his mind, body and soul likely stayed with him for life. Later records, including the Veterans Schedule of the U.S. Census (1890) notes that it was only nine months but that he suffered the effects of scurvy and rheumatism. Just weeks before the war ended on May 9, 1865, Hugh was released (April 20, 1865) and he mustered out at DeLaney House, D.C., on May 30 that year.

For the next three-plus decades, Hugh settled into his community of Battle Creek, where he worked as a farmer, laborer and later operated a draying business hauling goods throughout town, until his retirement. The 1880 census notes him as a laborer, living with Mary, Edward and Maggie (noted as a dressmaker) at 19 Beach Street (today known as Beach Street) in Battle Creek. The June 1990 census records him as a drayman living at 55 Beach Street with Mary; son Edward and his family lived just down the block at 47 Beach Street. A photo in the archives at Battle Creek’s Willard Library also shows that Hugh lived at some point on Liberty Street (not far from the north branch of the Kalamazoo River).

Some time in the 1890s, Hugh endorsed a noted Battle Creek doctor named Austin Samuel Johnson and his “electro-therapeutic cabinet” treatments as a cure for his eczema. It is likely that someone helped him with this testimonial given that Hugh was illiterate often simply signing his name with an X (as noted on his enlistment form).

“This certifies that about the first of November last I was taken with a severe attack of eczema, which confined me to my house and gave me intolerable suffering. Both of my legs below the knee became so swollen that I could not wear my boots or my ordinary under apparel, and my face was also swollen so that I could hardly see. My ears were so stiff that I could not bend them in the last. My flesh was covered with scales to such an extent that a dust pan was filled in the morning with what had fallen off during the night. The disease gave me constant chills, from which I could find no relief. I suffered the most excruciating distress and thought I was in the rebel prison at Andersonville for nine months, the horrors of that place gave me no such torture as I endured by this disease. Several physicians gave me their care, but without avail, until at length I applied to Dr. A. S. Johnson, two weeks ago, and his Electro-Therapeutic Cabinet gave me immediate relief and proved an effective cure for my disease. In the first two applications, my suffering was greatly relieved, and I have been steadily recovering since that time, so that I am nearly restored to my former health. The swelling of my limbs and face has subsided. I can now wear my boots and underclothing as usual, and I have no suffering whatever.” ~ Hugh Matthews.

Hugh was apparently fond of horse racing, and on at least one occasion was involved in the Battle Creek Driving Club as noted on the front page of the September 26, 1901, issue of the Battle Creek Daily Journal. During the “green race” – which was confined to local animals in half-mile, best three-out-of-five heats, Hugh was noted as the third-place winner.

About three months later, Hugh died of cystitis (inflammation of the bladder, most commonly caused by a bacterial urinary tract infection) on December 20, 1901, at the age of 71. He is buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery beside his wife, Mary (who had died of heart disease on January 31, 1901). Among the members of the Matthews family interred there (many in the family plot) include:

- Patrick (?-1864), father

- Margaret (?-1880), mother

- Edward P. (1857-1929), son

- Margaret (Matthews) Elizabeth Tobin (1858-1931), daughter

- Catherine “Katie” (1860-1871), daughter

- Mary (1862-1871), daughter

- Eleanor “Nellie” (1866-1871), daughter

- John (1868-1870), son

- Ann Donnelly (1834-1898), sister

- Michael Donnelly (?-1909), brother-in-law

- Bryan (1838-1879), brother

- Catherine “Kate” (Foy) Matthews (1847-1925), sister-in-law (Bryan’s wife)

- John Tobin (1854-1941), son-in-law

So, how exactly did Hugh’s story end up in the pages of The Penny – an historical novel about a Hall of Fame bowler and Scotch-drinking woman, her veteran fly-boy husband, and their family and friends?

“What I knew growing up was that Hugh was my great-great-grandfather who came over from Ireland prior to the Civil War, and entered the war in 1862,” recounts James. “His daughter, Margaret Elizabeth, married my great-grandfather, John Tobin, connecting those families. My second cousin, Patrick Tobin, has become the paternal family historian. He’s the one who told me about Hugh being at Andersonville.”

A self-proclaimed Civil War nerd, James said his interest in Andersonville and Hugh’s connections there were amplified when he learned his wife’s mother, Penny, was buried at the National Cemetery

“That’s how the story The Penny started to come together,” he says. “We did some research and sent paperwork to the park, and they registered Hugh into the Andersonville logs. The park staff continue looking for descendants of prisoners to tell their story. Then we looked at how serendipitous it was that Hugh and Penny were tied to one specific site – a horrific site for him, but a place of peace for her. That created a sense of balance and connection between our two families, which is the underlying magic of The Penny.”

Now, 120 years after his death, Hugh continues to inspire among others, his great-great-grandson.

“Hugh’s history finalized a perspective on how I became who I am – good and bad. No matter the befuddlement or crash, I was able to pick myself up and begin anew,” James notes. “He had to be that person, or he would never have survived the atrocities and become the well-loved man that he was to his family and friends.”

An outdoor lover and adventurer, James prides himself on pushing his limits and facing personal challenges head on.

“Hugh’s drive and perseverance set an example for me in so many aspects of my life,” says James. “From my two-month long kayak adventure along the shoreline of Lake Superior to bear encounters in the wilderness and other outdoor exploits that have tested me throughout my life, they pale in comparison to what my grandfather had to endure.”

James also reflects on Hugh’s survival in the POW camps really was a sacrifice – one that he had no control over – much like what the world has been forced into at the hands of the COVID pandemic.

“We grouse and claim hardship for being at home, with food, shelter, a place to sleep and diversions – understood, some have it better than others, but most have more than the earth beneath their feet,” James says. “My grandfather survived his many months at Andersonville, and I will survive this episode of history. If you’re able, recount the heroics of your family who built a better life for each generation. I guarantee, at some point in your family’s quest, there were circumstances that challenged the lineage. I toast Grandfather Matthews, and I toast my children as they, too, have learned hardships come and go. Breathe into the moment and care for the human inside you, and the humanity surrounding you.”

About the author…

Stewert James who has worked in law enforcement and various medical fields during his lifetime, was born into a military family in Alaska, where his father not only served in the Army but had volunteered for radiation testing as part of some form of nuclear testing during the Cold War. He dedicated nearly eight years to his service, including his reserve duty, dying of cancer in 1997. It is highly likely that his years of radiation exposure during his military service ultimately contributed to his death.

James’ father-in-law Bud Harper (on whom the character Frank in The Penny is based) served 27 years as an officer and pilot in the U.S. Air Force in which he attained the rank of Lt. Colonel. He was a decorated war veteran, serving in WWII and the Korean and Vietnam Wars. He saw many tours of duty, including: Rescue Crew Commander, Alaskan Air Command, Elmendorf AFB, AK; Continental Air Command, Robins AFB, GA; Air Force Detachment Commander, Qui Nhon, Republic of Vietnam; Instructor Pilot and Flight Examiner, Combat Support Group, Seventeenth Air Force, Ramstein AB, Germany; and Commander, Air Force ROTC, Michigan Technological University, MI. Among his commendations and decorations were numerous campaign medals, the Air Medal, Air Force Commendation Medal, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, and Small Arms Expert Marksmanship Ribbon.

In addition to The Penny – his sixth book – James has also penned Writing with Hemingway at City Park Grill: A Collection of Short Stories (a title credited to character Parker Moore in The Penny), and the bestselling SuperPac Trilogy (also featuring the autobiographical Parker Moore). He spent 42 years in healthcare as a practitioner, executive and lobbyist. For six years prior to retirement, he worked with adults of the Greatest Generation and heard their stories of life, happiness and survival. He and his wife, Christine, reside in the northern Michigan town of Petoskey, a stone’s throw from the majestic waters of Little Traverse Bay.