The American Robin Celebrates 90 Years as Michigan’s State Bird

A sure sign of spring…the return of the robins to Michigan!

In April 1931, the American robin (Turdus migratorius) was chosen as Michigan’s official state bird – one of three to claim this red-breasted aviary as its state bird (the others are Connecticut and Wisconsin).

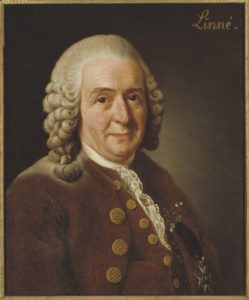

The term robin for this species was recorded as early as 1703. Years later, Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist and physician Carl Linnaeus (aka “father of modern taxonomy”) first described the species in print in his twelfth edition (1766) of Systema Naturae – a binomial name derived from two Latin words: Turdus (“thrush”) and migratorius (from migrare, “to migrate”).

Early colonists referred to this migratory songbird simply as “robin” and it reminded them of a beloved English bird of the same species. According to the Partners in Flight database (2019), the American robin is the most abundant bird in North American (370,000,000). Seven subspecies of the American robin are recognized throughout the country.

Michigan is home to 450 species of birds, under various classifications according to the Michigan Bird Records Committee. Among those, the robin is the most common backyard bird during the summer months (62%) followed by the song sparrow, American goldfinch, mourning dove, blue jay, northern cardinal, common grackle and black-capped chickadee.

As you could imagine, picking just ONE of these feathered friends as our Michigan state bird wasn’t an easy task (and remains a matter of contention even today).

In early 1929, the Michigan Audubon Society (MAS) organized a contest asking residents to vote for this esteemed recognition (which meant sending in letters or postcards to cast a vote) as a way to celebrate its 25th anniversary.

An article in the March 11, 1929 Battle Creek Enquirer read “A lively campaign is on among Michigan’s bird residents as to which shall be the official state bird. Primaries were held last October when a committee of the Michigan Audubon society selected 21 candidates from a field of 326 possible candidates. Election notices have been received by the local Audubon society stating that the polls will be open from April 1 to April 16 [which was later extended to April 20 and then May 1] and everyone in the city is entitled to a vote in choosing the state bird.”

The list of “candidates” included:

- Chickadee

- downy woodpecker

- bob-white, goldfinch

- red-winged black-bird

- meadowlark

- song sparrow

- robin

- bluebird

- bob-o-link

- brown thrasher

- catbird

- Baltimore oriole

- Kingbird

- cedar wax-wing

- mourning dove

- house wren

- whippoorwill

- rose-breasted grosbeak (generally called the cardinal redbird, according to an article published on March 31, 1929 in the Detroit Free Press).

“No doubt if the birds knew of the contest, each species would endeavor to make as favorable an impression as possible during the next few weeks. There would be sweeter songs, and earlier returns from the south. There might even be campaign slogans, such as Be Happy with the blue-bird or Cheerful with the Chickadee,” the article continued.

Editorials even appeared in Michigan newspapers urging residents to vote for one bird over another. Under the headline “Bluebird Praised Next to Robin” which appeared March 13, 1929 in the Battle Creek Enquirer, T. Ben Johnson, Scout Executive shared his thoughts:

“After the robin, which he names as his choice for Michigan’s state bird, Scout Executive T. Ben Johnson prefers the bluebird, because of its beautiful plumage and pleasing manners. Its bright blue wings and tail, gentle manner, simple but melodious warble, and early returns from the south make it a much loved bird.”

Another editorial appeared March 19, 1929 in the Ironwood Daily Globe (originally published in the Detroit News.

“It is sincerely hoped that the final choice will not be based solely upon acquaintanceship but rather upon this combined with the economic importance of the species, its song, habits, disposition and appearance, and knowledge of its worth as compared with other birds associates. Everyone is on speaking terms with the robin, wren and bluebird, but few know the Kirtland warbler, chickadee or grosbeak, and for this reason, the contest should inspire a close study of the unfamiliar species so that they may be treated fairly.”

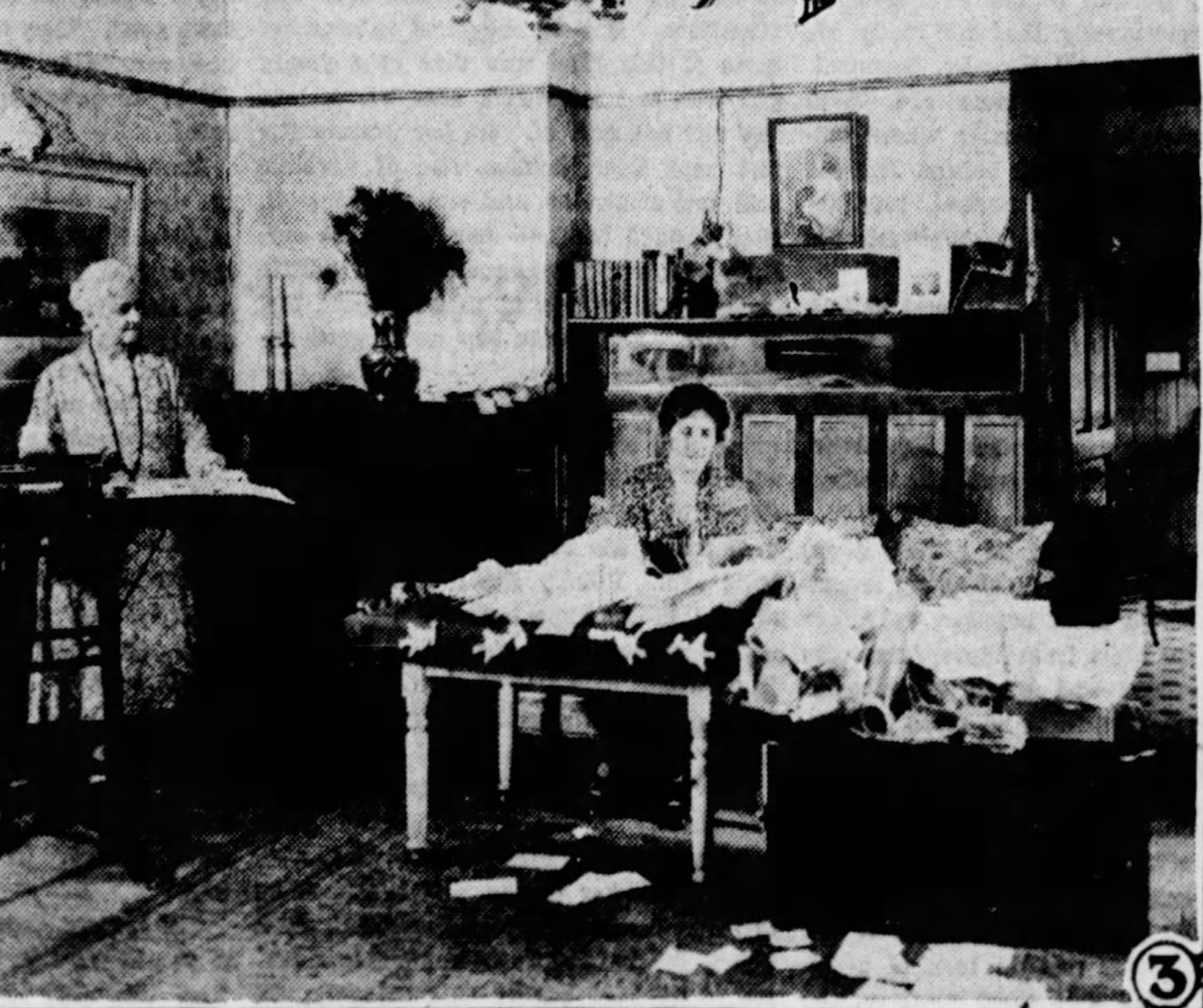

Throughout April 1929, individuals and organizations around the state – clubs, social groups and even school children – rallied to mail in their votes (each adorned with a 2-cent first-class stamp) to a residential address in Hart, Michigan – where they were collected for tallying.

“The state legislature will put its official stamp on the choice of the bird made by the people,” says Mrs. Lucretia T. Norgaard, of Hard, secretary and treasury of the Michigan society was quoted in a 1929 article. “Who will be selected to introduce this measure has not been decided, but some of the members of the legislature are members of this organization. Our society believes this selection of an official state bird would be a good way of celebrating our twenty-fifth anniversary.”

When all was said and done, nearly 185,000 people voted, with the robin raking in nearly a quarter of the votes (45,541) followed next by the chickadee (37,155), blue bird (17,024), goldfinch (15,866), cardinal (12,288), quail (9,792), Baltimore oriole (6,355) and house wren (5,433).

With their results in hand, MAS asked the Michigan legislature to officially adopt the robin as the state bird. On Wednesday, April 8, 1931, Representative Conrad Netting of Detroit, chairman of the conservation committee, introduced House Concurrent Resolution 30 which declared it so.

Yet, chickadee fans have continued to chirp about this topic for the past nine decades – with proponents claiming that unlike the robin, the chickadee isn’t a “snowbird” and that it sticks around the Great Lakes State all year long.

As recent as 2000, there was a bill introduced to oust the robin and name the chickadee as the official state bird. Headlines on April 4, 2000 read “Features are flying over our state bird – Robin-bashing chickadee boosters seek change” (Herald Palladium, St. Joseph/Benton Harbor) and “Chickadee-for-state-bird effort relaunched” (Petoskey News Review). Apparently, legislation to replace the robin had been drafted that year, but was waiting a sponsor.

“I’m very much in favor of it,” Tom Symons of Petoskey [who came to the area to manage Boyne Mountain in 1956, later served as director of the Charlevoix Chamber of Commerce and founded Symons General Store in downtown Petoskey] noted in the News Review article. “The chickadee is around all year, and it is the most friendly bird. I have had them land on my hat when I’m out filling the feeder.”

Symons did more than simply express his support of the chickadee, he printed 100 petitions to gather signatures in support of the second-place bird, although he noted “the robin is so entrenched, they will have a hard time replacing it.”

Much like efforts in 1950 (which garnered 15,000 petition signatures statewide) and 1992 (where a bill was introduced but died before reaching the House floor), things stalled once again for the chickadee in 2000.

But things weren’t quite for long.

In 2003, another attempt to overtake the top spot was initiated by fans of the yellow and black colored Kirtland’s warbler – a bird exclusive to Michigan.

The Kirtland’s warbler was first identified in 1851 but wasn’t known to be unique to Michigan until 1934.

There was an effort in the early 1970s to crown this unique bird as Michigan’s official representative, but by that time the population was dwindling at an alarming rate due to loss of habitat for nesting (in the jack-pine forests) as well as infestation of cowbird (nest parasites that lay eggs in the warblers’ nests). In 1967, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service added the Kirtland’s warbler as an endangered species.

Thankfully, conscious efforts in conservation and revitalization lead to a population recovery of the Kirtland’s warbler from fewer than 200 breeding pairs in the 60s to around 2,300 pairs today (found in 10 counties in the northern Lower Peninsula and four counties in the Upper Peninsula).

Yet, even with its population return, it wasn’t able to dethrone the robin – which has remained the top bird in Michigan now for 90 years!

For more about birding in Michigan, including a list of sanctuaries and trails, check out: Pure Michigan…it’s For the Birds!

To hear the call of a robin, visit AllAboutBirds.org. Featured photo: National Audubon Society.