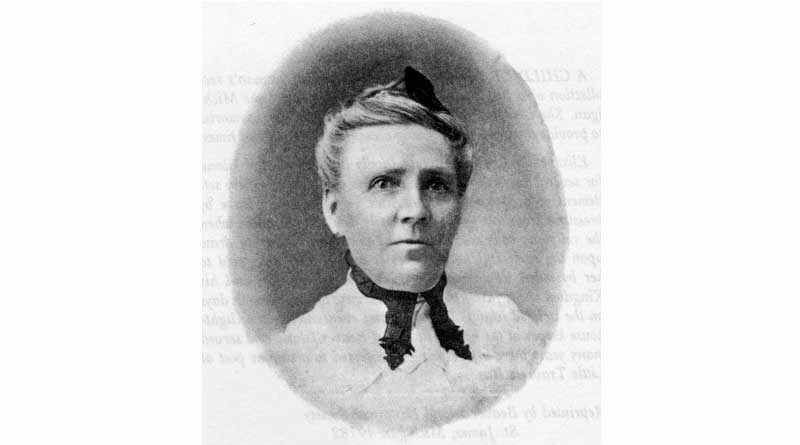

An Illuminating Lady – Elizabeth Whitney Williams

By Dianna Stampfler

A Child of the Sea was a more than just the title of Elizabeth Whitney Williams’ 1905 autobiography – it was an accurate moniker for the Michigan-born woman who became one of the longest-serving lighthouse keepers in the entire Great Lakes region. One of her earliest recollections was wandering down to the coastline to gaze upon the vastness of the freshwaters before her. It entranced her then just as it did for the ninety-plus years of her life living in Michigan.

“I remember standing with my arms outstretched as if to welcome and catch the white topped waves as they came rolling in upon the white, pebbly shore at my feet,” Elizabeth recalled of her toddler years.

The curious child learned early on the importance of these inland seas as she and her family traveled from one port town to another to live and work. She recognized what a gift it was to live so close to the shore, but she also knew firsthand the dangers that lingered when then wind and weather churned those waters into a deadly frenzy.

Born on Mackinac Island on June 24, 1844, Elizabeth was the only child of Elizabeth Cross Dousman Gebeau (1796-1896) and Walter Whitney (1809-1870). Her mother was the orphan child of Angelica (noted as a local Native American woman) and John Cross (French by some accounts and British by others), both of whom died when she was an infant.

Prominent Mackinac businessman Michael Dousman, and his wife, Catherine Jane Aiken McDonald, adopted Elizabeth Cross and raised her alongside their ten biological children. Dousman was an agent for the John Jacob Astor Fur Company, owning significant tracts of land throughout the Straits of Mackinac – including what is now Historic Mill Creek in Mackinaw City and parts of Bois Blanc Island in northern Lake Huron.

Elizabeth Cross’ first marriage to Louis Gebeau, from which four sons were born (Louis, Antoine, Charles and an unnamed son who died), ended tragically when Louis drowned in an 1841 boating accident on Lake Michigan. Sadly, he wouldn’t be the first member of this family to lose his life in the freshwaters of the Great Lakes.

New York born Walter Whitney enlisted, served and was honorably discharged from the Blackhawk and Florida War, going next to Fort Brady in Sault Ste. Marie before relocating to Mackinac Island, where he met widow Elizabeth Gebeau. The two wed in 1843 and the following year welcomed their first and only child, Elizabeth (sometimes also called Lizzie, even into her adulthood).

A builder by trade, Whitney soon moved his family of six west from Mackinac Island to the 266-acre St. Helena Island where brothers Archibald “Archie” and Wilson Newton were establishing a commercial fishing operation.

“They [the Newton brothers] needed a good vessel for their trading purposes and concluded to have one built for themselves. My father being a ship carpenter, signed a contract to build their ship, which was to be named ‘Eliza Caroline,’ in honor of both brothers’ wives, who were sisters. And long the ‘Eliza Caroline’ sailed on Lake Michigan, carrying 13 thousands of dollars worth of merchandise and fish, doing her work nobly and well. The building of the ship brought our family to the dear little island of St. Helena,” Elizabeth wrote in her autobiography.

The October 16, 1850, census noted that the Whitney family – including a six-year-old Elizabeth – was living on St. Helena Island, in Michilimackinac County. Not long after, they headed to Manistique along the northern shore of Lake Michigan in the Upper Peninsula for the winter.

“My father was sent for from Manistique,” Elizabeth wrote. “A Mr. Frankle had settled there and put in a mill. He was an old friend of my father’s, coming from Chegrin Falls, Ohio. Offering good pay, father concluded to accept, and we prepared to move at once. The schooner Nancy, also owned by the Newton Brothers, was to take us to our destination…One still, cold morning in November our boat was prepared and we started to Manistique, ten miles distant.”

Their time in the Upper Peninsula was short lived, but full of adventures that lead to many happy memories that Elizabeth recounted in the pages of her book. But it would be their next destination that would really shape her life.

Beaver Island in the 1850s was home to a growing congregation of Mormons lead by self-proclaimed King James Strang. It was here that the Whitneys landed and where Walter subsequently found work building a “cottage” for the king and his increasing number of wives.

“About this time King Strang decided to build a residence for himself. He made the plans and called it the ‘King’s Cottage.’ The King came to our house asking my father to go to the harbor and help build his house. He wanted him to do the framing, and father, not being very busy, and not liking to refuse the King, went. Father was gone about six weeks, coming home often to see how we were at home. He boarded at the house where there were four wives,” Elizabeth recalled.

These years under Strang’s reign were tumultuous for the Whitneys and many others on Beaver Island. Given the growing volatility, Elizabeth and her brothers were often sent to live with others for their own safety. About age eight or nine, Elizabeth temporarily lived with the Milton A. Shephard Family of Painsville, Ohio (not far from where her brother Charley was boarding at the time, and ultimately near where he passed away in 1914 at the age of 73).

For a brief period of time, the Whitneys relocated to Traverse City, where Elizabeth was excited to continue her education. The first school here (noted as the first in the Lower Peninsula north of Manistee to not be connected with a mission) operated in 1853 in a converted stable on the 400 block of East Front Street.

“The school house was near the river bank, just about opposite to the river’s mouth. It stood back far enough for a good wide street. It was in the midst of a pretty grove of small oak trees that reached their branches far out, giving cool shade where we could sit and eat our lunch. The evergreens and maple trees were mixed about, giving it a variety of change. Wild roses grew everywhere. It was truly an ideal spot that we never tired of. Our teacher was Miss Helen Goodale,” Elizabeth noted. “The next year more people came and more scholars. Our little school house was filled. We were a happy lot, seeming almost like one family. We drank from the same cup, swung in the same swing, sharing our lunches together, and no matter where we have roamed through the wide world can we forget that little old log school house. I have seen it many times in my dreams, and the happy faces of each as we tried to excel to please the teacher. We all loved her, though trying her patience often. Yet we knew and felt she loved us. Oh, happy school days and pleasant school companions!”

During their time in Traverse City, Walter Whitney adopted a seven-year-old boy named Frank Churchill, whose mother had passed away and whose father couldn’t care for him and his siblings. Having a younger brother pleased Elizabeth, especially since her older brothers were soon grown and living on their own.

When news came in June 1856 of Strang’s assassination, the Whitneys (including Frank and a then twelve-year-old Elizabeth) felt it was finally safe to return to Beaver Island. Elizabeth quickly settled into a life with friends and school, and age sixteen (1860) she married Clement VanRiper (who was twelve years her senior).

“I was now married to Mr. Van Riper and living very near the light-house,” Elizabeth wrote. “My husband had come from Detroit for his health. After we were married he started a large cooper shop at the Point, employing several men in the summer season.”

After spending the winter of 1861 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Clement and Elizabeth returned to the Beaver Island archipelago – specifically Garden Island to the north, which was inhabited at the time by about 200 Indians, who fished and grew corn and potatoes.

“In July of 1862 my husband was appointed as a Government school teacher to the Indians at Garden Island. The school was a large one as there was a large band of Indians. Our school continued for two years, then was discontinued for several years before another teacher was sent among them. That two years was a busy life for us both.”

The next noteworthy profession for Clement and Elizabeth would be one that would last each of them a lifetime. Following the August 1869 resignation Peter McKinley, Clement was named the head keeper of the St. James Harbor Light at Whiskey Point – at a salary of $540 a year. Elizabeth had turned 25 earlier that summer and she was excited for the new home and all the responsibilities that came with it. As Clement continued to suffer with health issues and was often unable to fulfill his duties, Elizabeth willingly served in his stead.

“From the first the work had a fascination for me. I loved the water, having always been near it, and I loved to stand in the tower and watch the great rolling waves chasing and tumbling in upon the shore. It was hard to tell when it was loveliest. Whether in its quiet moods or in a raging foam.”

Just a little over three years after his appointment, Clement’s service came to an abrupt end. On the evening of November 7, 1872, the schooner Thomas Howland was caught in a storm and took on water, causing her to sink. Clement had rowed out in his boat, attempting to help the crew, but both he and the first mate died and their bodies were never recovered. Twenty-eight-year-old Elizabeth was left widowed, heartbroken and distraught about how she would move forward in life.

“Life to me then seemed darker than the midnight storm that raged for three days upon the deep, dark waters. I was weak from sorrow, but realized that though the life that was dearest to me had gone, yet there were others out on the dark and treacherous waters who needed to catch the rays of the shining light from my light-house tower,” Elizabeth lamented. “Nothing could rouse me but that thought, then all my life and energy was given to the work which now seemed was given me to do. The light-house was the only home I had and I was glad and willing to do my best in the service. My appointment came in a few weeks after, and since that time I have tried faithfully to perform my duty as a light keeper. At first I felt almost afraid to assume so great a responsibility, knowing it all required watchful care and strength, with many sleepless nights. I now felt a deeper interest in our sailors’ lives than ever before, and I longed to do something for humanity’s sake, as well as earn my own living.”

Elizabeth was soon appointed as the head keeper of the Whiskey Point Lighthouse – a common practice for the wives of keepers who died in the line of duty. In 1875, she married a local cooper named Daniel Williams, who has also been born on Mackinac Island (seven years after Elizabeth). The couple maintained their lighthouse keeping for nearly a decade on “Michigan’s Emerald Isle” but in 1884, Elizabeth desired to move to the mainland and petitioned for a transfer from the U.S. Lighthouse Service.

Some 31 miles southeast of Beaver Island, a lighthouse was being constructed on a three-and-a-half acre parcel at the end of a 50-acre peninsula in the town of Little Traverse (the original name of Harbor Springs) where The Harbor Point Association had been formed just six years prior (August 28, 1878). Workmen and materials arrived on the point on May 14, 1884 and just 96 days later it was put into service. Elizabeth became the first of just seven keepers here, with an annual salary of $540 to $560.

“Next morning we drove through the resort grounds to ‘Harbor Point Light House,’ as it is known by the land people, but to the mariner it is ‘Little Traverse Light House,’” Elizabeth remembered of that day. “We were soon at work putting our house in order, and the beautiful lens in the tower seemed to be appealing to me for care and polishing, which I could not resist, and since that time I have given my best efforts to keep my light shining from the light-house tower.”

For nearly three decades, Elizabeth and Daniel called the two-story brick lighthouse at Harbor Point their home. And while she kept the light burning, Daniel ran a successful photography studio in town (several of his original images are in the collection of the Harbor Springs History Museum). Elizabeth had no children, but she and Daniel had a great number of friends, and they often hosted musical gatherings at their home. Both were well tuned musicians, playing a variety of instruments which likely helped pass the time at the lighthouse.

On November 1, 1913, Elizabeth officially retired after serving 44 years between the Beaver Island and Harbor Springs lighthouses. The couple then moved nearly 30 miles down the coast to Charlevoix, where just a few years prior Elizabeth had purchased a house (at present day 405 Michigan Avenue). In 1925, they moved once again to 303 Mason Street, where they lived until they passed away on January 23, 1938 – within twenty-four hours of each other (Daniel, 87, first, followed by Elizabeth, 93). They had been married for 63 years.

Brookside Cemetery, at the intersection of US-31 and M-66 south of downtown Charlevoix is the final resting place for Elizabeth and Daniel. Their headstones that read “Aunt” and “Uncle” were chosen by Harry Gebeau, grandson of Elizabeth’s half-brother Louis.

Louis passed away in 1887 when the steamer Vernon sank off the cost of Manitowoc, Wisconsin. He is also buried in Brookside Cemetery, alongside his widow, Eliza Jane; his grandson Harry (Harrison Edgar) and Harry’s wife, Mary Alice; his great grandson, William (Bud) and Bud’s wife, Virginia.

Elizabeth’s father, Walter, passed away in 1870 at the age of 61 and is buried in Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Her mother, Elizbeth, died in 1896 – just two months shy of her 100th birthday. She is interred in the Lakeview Cemetery in Harbor Springs.

In Michigan’s nearly 200 years of lighthouse history, some fifty or so women have served as keepers or assistant keepers, yet it is Elizabeth who boasted the longest career and the most colorful history. She is also the only female keeper to pen such a detailed autobiography which shares stories not only of her professional life but that of growing up in the mid nineteenth century.

A Child of the Sea can be downloaded online for free reading from Gutenberg.org or ordered from your local bookstore or library.

Dianna Stampfler is the president of Promote Michigan and the author of Michigan’s Haunted Lighthouses (2019) and Death & Lighthouses on the Great Lakes (2022), both from The History Press.