Shedding Light on Michigan’s Historic Female Keepers

It may be no surprise that Michigan has more miles of freshwater coastline than any other state or that the Great Lakes State has more lighthouses than any other in the country (at about 120). But did you know that more than 60 women have been documented as lighthouse keepers at these historic beacons?

In fact, serving as a lighthouse keeper was the only “non-clerical” government job that women were allowed to have in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Ironic since it was quite a grueling and physically demanding career.

Often, these women served as assistant keepers with their husbands, fathers or brothers—and in the case of tragedy, many were promoted to the role of head keeper.

Here are the stories of some of Michigan’s most noted female keepers.

JULIA (MOORE) SHERIDAN – SOUTH MANITOU ISLAND LIGHT, SLEEPING BEAR DUNES NATIONAL LAKESHORE

Aaron Sheridan was injured during his service in the Civil War—the bones in his lower left arm shattered during the Battle of Ringgold, and he was later appointed as the lighthouse keeper at South Manitou Island on July 21, 1866. His wife, Julia, was appointed his assistant on September 30, 1872 and together they tended the light and raised their six sons on the remote island 16 miles west of Leland, in northern Lake Michigan.

On March 15, 1878, Julia and Aaron, along with their infant son, Robert, were returning aboard a small boat from the mainland when their boat capsized just off shore. Aaron, with his one arm, was unable to save himself, his wife or his son. The only survivor was an island fisherman by the name of Chris Ankerson, who owned the boat in which they were all traveling.

To magnify the tragedy, the two oldest Sheridan sons — Levi, age 12 and George, age 10 — were in the lighthouse tower and witness the horrific accident. All three were lost to the inland sea and the brothers are said to have walked the island shoreline for weeks, with hopes the bodies would wash ashore. The five brothers (the younger siblings being James, age 8; Alfred, age 6 and Charles, age 3) were sent to Illinois to be raised by their grandparents, Henry and Julia Moore. George became a lighthouse keeper himself, serving in Chicago, Michigan City and Saugatuck (with his wife, Sarah), before taking his own life after years of depression and mental illness resulting from the loss of his parents and brother.

It wasn’t until 2006 historical grave markers for the three were placed on the now-deserted island, when descendants of Julia and Aaron were able to secure permission. You see, markers are not allowed to be placed in National Parks—however, given that Aaron was veteran of the Civil War, an exception was eventually made.

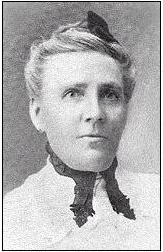

ELIZABETH (WHITNEY) VANRIPER WILLIAMS – ST. JAMES HARBOR LIGHT, BEAVER ISLAND

Elizabeth Whitney was born to English parents on Mackinac Island in 1844, but moved as an infant with her family (four half-brothers from her mother’s first marriage) to St. Helena Island and then Beaver Island. At this time, the Mormon community was thriving on the Beaver Island, under the often the tumultuous ruling of self-proclaimed “King” James Strang.

Elizabeth Whitney was born to English parents on Mackinac Island in 1844, but moved as an infant with her family (four half-brothers from her mother’s first marriage) to St. Helena Island and then Beaver Island. At this time, the Mormon community was thriving on the Beaver Island, under the often the tumultuous ruling of self-proclaimed “King” James Strang.

Around the age of five years, Elizabeth and her family were exiled from the island for not conforming to the religious code set forth by Strang (who was later assassinated by his own people). In later accounts of the incident, Elizabeth recalled that even at the young age remembering the fear and tension that her family lived through at this time. After growing up on the mainland, Elizabeth returned to Beaver Island in the 1860s following her marriage at the age of 18 to Clement VanRiper.

It was 1869 when Elizabeth’s husband, Clement, was appointed the head lighthouse keeper at the St. James Harbor Light on Beaver Island, at Whiskey Point. She would have been 25 years old at the time. Soon after his appointment, Clement took ill and Elizabeth stepped in to assist with the responsibilities. It was a job she quickly took to and found a deep passion for.

“I took charge of the care of the lamps; and the beautiful lens in the tower was my especial care. On stormy nights I watched the light that no accident might happen…From the firs the work had a fascination for me. I loved the water, having always been near it, and I loved to stand in the tower and watch the great rolling waves chasing and tumbling in upon the shore.” (p. 213). – A Child of the Sea & Life Among Mormons, Elizabeth Whitney Williams.

In 1872, tragedy struck Elizabeth and the entire Beaver Island community when Clement died while trying to rescue the crew of the schooner the Thomas Howland, which had taken on water and eventually sank in the harbor. A distraught Elizabeth – who had lost other relatives on the deep Great Lakes waters – found solace in devoting her life to tending the light so that she might have some role in preventing future loss.

“Life to me then seemed darker than the midnight storm that raged for three days upon the deep, dark waters. I was weak from sorrow, but realized that though the life that was dearest to me had gone, yet there were others out on the dark and treacherous waters who needed to catch the rays of the shining light form my light-house tower. Nothing could rouse me but that though, then all my life and energy was given to the work which now seemed was given me to do. The light-house was the only home I had and I was glad and willing to do my best in the service…At first I felt almost afraid to assume so great a responsibility, knowing it all required watchful care and strength, with many sleepless nights. I now felt a deeper interest in our sailors’ lives than ever before, and I longed to do something for humanity’s sake, as well as earn my own living.” (p. 215). – A Child of the Sea & Life Among Mormons, Elizabeth Whitney Williams.

Elizabeth took great pride in her job as lighthouse keeper and was known throughout the service as having one of the greatest records of service and was even awarded a prize for the best kept light. She remarried in 1875 to a man named Daniel Williams, retaining her position as lighthouse keeper on Beaver Island until 1884. At that time, at the age of 40, she requested a transfer to a mainland station in Harbor Springs – at the newly built Little Traverse Lighthouse. In September of that year, Elizabeth walked the staircase to the tower to light the beacon for the first time.

“We were soon at work putting our house in order, and the beautiful lens in the tower seemed to be appealing to me for care and polishing, which I could not resist, and since that time I have given my best efforts to keep my light shining form the light-house tower.” (p. 224). – A Child of the Sea & Life Among Mormons, Elizabeth Whitney Williams.

She was nearly 70 years old when she retired from the lighthouse service in 1913 (some research, including her obituary, indicate that she retired in 1906). She and Daniel moved south to Charlevoix and became active members of that community until they died within 28 hours apart from each other in January 1938.

Read more about Elizabeth in her autobiography, A Child of the Sea & Life Among Mormons.

ANNA MARIA CARLSON – APOSTLE ISLANDS, LAKE SUPERIOR

Anna Maria Carlson was the wife of Robert Carlson, and the couple served at various lights between 1891 and 1931 including Outer Island (1891-1893), Michigan Island (1893-1898), Marquette (1898-1903) and Whitefish Point (1903-1931). One particular story was recounted by Anna herself in the May 17, 1931 issue of the Detroit News:

“We were trying a winter on Michigan Island, where my husband was head lighthouse keeper. His brother was assistant. When we decided to stay, our hired girl promised to remain with us through the winter. But she slipped away and went ashore with some fishermen and didn’t come back.

(One day) they took the dogs and went fishing. I was always afraid to be alone on the island. A city-bred girl, the stark loneliness of it was appalling. As soon as they left the house I ran about and locked all the doors and windows. Yet there was nobody on the island but myself, and the children, a little girl past two, and the twin boys, nine months old.

For a few hours after they had gone that day I was busy setting the house in order. The tower was closed but there was lots of work to do in the house, and I was glad for that. I got the children’s lunch, prepared things for an early supper, as I knew the men would be very hungry when they came home, and then sat down to wait.

Women who wait in brightly lighted cities with people all around within call of the voice have no conception what it is to sit and wait for your man on a deserted island, with snow and ice everywhere and no light but the stars. I watched the sun go down across the water, waited until its sickly yellowish light had disappeared and the stars came out.

I kept stoking the fires, for I knew the men would be cold when they came in. I did not even think of such a thing as their not coming. They had been gone since before daylight, and they would be home before six, I was sure. The wind was blowing a gale, but in my ignorance of such things I gave it no thought.

Six o’clock came, and darkness. It was so dark outside I could not bear to look out the window, but I kept watching for the men and the dogs. It began to snow. Seven o’clock and still my man had not come. I put the children to bed and waited.”

Read more of Anna’s story here.

JULIA (TOBY) BRAWN WAY – SAGINAW RIVER LIGHT

Julia Toby Brawn was married to Peter Brawn, the Saginaw River Light station’s eighth keeper. They moved into the dwelling with their son, Dewitt, on March 16, 1866. The following year, Peter suffered an unrecorded injury or disease and became completely incapacitated as a result. Thus, unable to tend the station, Julia took over Peter’s duties on an unofficial basis, with the assistance of Dewitt.

While this fact would have been clear to the District Inspector when conducting his inspections of the station, the situation was apparently overlooked since while Peter was completely bed-ridden, he continued to appear as the keeper of record at the Saginaw Bay Light in district payroll records.

Finally succumbing to his illness, Peter passed away on March 18, 1873 and after 7 years of tending the light in an unofficial capacity, Julia was officially appointed to the position of Head Keeper. She married George Way in 1875 and within two years, she was demoted to assistant keeper, with George being appointed head keeper. The assistant position was abolished in 1882, at which time Julia discontinued all official service.

Whether the District office undertook this change in an attempt to pressure George and Julia into resigning, or as an underhanded attempt to reduce costs, is undocumented. However, it is likely that some plan was afoot, since on George’s death on February 10, 1883, Julia disappeared from lighthouse service and the keeper roster at the station was again increased to include both a keeper and assistant. Julia herself died in 1889.

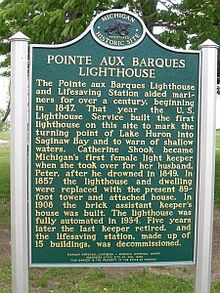

CATHERINE SHOOK – POINT AUX BARQUES, PORT HOPE

Catherine Shook was appointed acting keeper at the Point Aux Barques lighthouse from 1849 until 1860 following the death of her husband, Peter (who was the station’s first keeper, appointed in 1848). In addition to tending to the light, she raised her eight children at the light.

Shortly after the death of her husband, Catherine and the children survived a fire in the keeper’s dwelling, between the kitchen ceiling and roof. Following this fire, Superintendent and Inspector of Lights Henry B. Miller investigated the incident, placing blame on a faulty chimney. He subsequently sent a report to his superior, stating:

“The circumstances of this fire is the more to be regrettable as the husband of the keeper but lately found a watery grave in Lake Huron, and this affliction on this account falls with a double severity upon the widow who was lately appointed in his place. By this catastrophe, the widow not only lost a considerable portion of her furniture, but was badly burned in her attempt to keep the fire from the main building. They have erected temporarily a small shanty, which is very uncomfortable and unhealthy. I therefore hope that no time will be lost in having the dwelling rebuilt.” After another visit to the lighthouse on July 2, 1850, Henry B. Miller reported: “Everything in passable order. Conduct of keeper good.”

Although Catherine was performing her duty well, the strain of keeping a light and caring for her children may have been too much as she resigned her position on March 19, 1851. She passed away nine years later and was buried next to her husband in Oakwood Cemetery in New Baltimore, Michigan.

Other female keepers included:

- Caroline Litigot Autaya was appointed keeper of the no-longer-standing Mamajuda light on January 8, 1874, following death of husband, Barney. Removed on July 1 of that year but was reinstated two months later after outrage by the locals. Caroline served until May 28, 1885 (having remarried in 1876).

- Jennie Beamer was named acting first assistant of the Big Bay Point Lighthouse near Marquette during the summer of 1898 while husband, George, served in Spanish/American war. On May 14, 1898, it was noted in the keeper’s log that a letter had been received stating that “any employee that wished to volunteer for Army or Navy during war would have his position held for him for 12 months.” George Beamer left at once for Detroit, and Jennie was appointed laborer at the station. The log for June 10, 1898 read: “Major M.B. Adams inspected station, Mrs. Beamer retained as labor/acting assistant.” On August 26, the log stated that George returned from Navy service, releasing his wife from duty as acting assistant.

- Mary Beedon was acting first assistant keeper form July to October 1876 under husband, Napoleon. The “acting” was then dropped and she served until 1879 when they both resigned.

- Henrietta Bergh was the first unofficial keeper at the Mendota on Lake Superior, before a light at Bette Gris was completed in 1895. Stories have been passed down that Henrietta would put a lantern in the upper window of her home on the nights when her husband was out late fishing and that before long, other fishermen in town asked her to do the same for them. When the light was completed, it made sense for Henrietta to be appointed its first keeper.

- Rene Bouchard as noted as assistant keeper of the Manitou Island light from April 1856 until February 1859.

- Nellie Buzzard worked at the Saginaw River Light from 1883 until 1886 with her husband, Edward. The couple was evidently ill-suited to the rigors of lighthouse keeping, as they both simultaneously resigned their respective positions after only three years of service at the station. They were the last husband/wife team to serve at this lighthouse.

- Annie M. Carlson was acting assistant at Granite Island light for nine days in 1905, following the tragic death of assistant keeper, John McMartin.

- Slatira Carlton was named keeper of the St. Joseph lighthouse from November to December 1861, following death of husband Monroe.

- Sarah Caswell was acting first assistant of the Big Sable Point Lighthouse from May 16, 1874 to September 29, 1875 under husband Burr, before being appointed first assistant until December 4, 1882.

- Mary Cocking was first assistant under her husband, Stephen, at both the Gull Rock and Manitou lights between September 12, 1872 and July 27, 1877.

- Mary (Raher) Corgan was an assistant keeper from 1873 and 1875 with her husband, James. They served at both Manitou Island Gull Island, where they were transferred to in 1877. There is an interesting story about the birth of their second oldest, James P “Budd” Corgan, in the 1870s. Mary died in 1893 after some sort of surgery at a hospital in Milwaukee. James married Josephine Dolan and had 4 more children.

- Anne Crebassa was appointed acting keeper of the Sand Point Lighthouse between March 29 and May 12, 1908 after death of husband, John.

- Jane Enos was appointed acting keeper of the St. Joseph lighthouse from 1876-1878 (and primary keeper until 1881) following the death of her husband, John. For nearly three years, she had a male assistant keeper—which was virtually unheard of in that era.

- Mary Garraty was first assistant keeper from 1872 until 1882 at the Old Presque Isle Lighthouse on Lake Superior, under her husband Patrick Garraty Sr. He was the last keeper at the old lighthouse and the first at the new light, which opened in 1870. The Garraty’s four children—Thomas, John, Patrick Jr., and Anna—all served at various times at the area lights. Anna served at the New Presque Isle Light as well as the Range Lights from 1903 until 1926.

- Mary Gigandet was acting first assistant in 1892 and 1983 at the Au Sable Point Lighthouse under husband, Gus. The “acting” was then dropped and she served until 1897, one year after his death.

- Mary Granger served head keeper at the Bois Blanc lighthouse from February 25 to July 16, 1857 following death of husband, Henry. She found the job to be too difficult and resigned after just five months.

- Julia Ann Griswold served as acting keeper of the Eagle River lighthouse from 1861 to 1865 following death of husband, John.

- Donald Harrison served one month as a keeper of the St. Mary’s River light in 1902.

- Harriet Howard was acting first assistant at Charity Island light in 1877 and 1878 under husband, Charles. Son, George, was acting fist assistant prior. The “acting” was removed in 1878 and she served until 1879 when both she and Charles resigned.

- Nancy Hume was first assistant at the Skillagalee light in northern Lake Michigan from November 8 to 20, 1869 under husband, Robert. They both resigned at that time.

- HG Hunter was acting keeper at Little Sable Point Lighthouse in Mears from February 15 to March 11, 1910 while husband, J. Arthur Hunter, was on undisclosed temporary leave.

- Elsea Hyde served as first assistant at the Big Sable Point Lighthouse in Ludington from January 29, 1869 until March 22, 1871 under husband, Alonzo W. Hyde – son of first keeper, Alonzo Hyde Sr.

- Frances Wuori Johnson was a civilian keeper of the White River Light Station in Whitehall during the 1940s, with husband Leo Wuori. He left to return to the Upper Peninsula, but she stayed on until 1954. She was also featured on the television show “What’s My Line?” in 1953, where she stumped the panel and received a prize of $50 (plus the trip to New York City).

- Emma Kahn served for two months as first assistant at the Sand Point light in 1907 under Emmanuel Luick, although there is no record of a Mr. Kahn serving there. This was after Emmanuel’s wife, Ella, had left the island permanently (see below).

- Sarah E. Lane served as an assistant keeper with her husband, John, at St. Clair Flats South Channel Range Lights in southwest Michigan, before moving to the Old Mission Point Lighthouse in 1878 as that light’s first keepers. Sarah assisted with duties during John’s poor health and following his death on December 12, 1906. She left the post in early 1907.

- Anna Larsen was assistant keeper to her husband, Lewis, at the Raspberry Island light between 1868 and 1880.

- Ivory Littlefield served one month (August 31-October 1, 1894) at the Cheboygan Range Light following death of her husband.

- H. Lubuck was first assistant of record at the Grand Island East Channel light from May 12, 1862 until May 22, 1865 under keeper George Wagner. No record of where Mr. Lubuck was, as is doesn’t show up on the lighthouse records.

- Ella Luick served as an acting keeper of the Sand Island Lighthouse on Lake Superior between 1901 and 1904, with her husband Emmanuel. She lasted 10 years on the island, but on May 19, 1905, she left the island, never to return.

- Katherine “Kate” Marvin was named keeper of the Squaw Point Lighthouse in northern Lake Michigan in from 1897 until 1904 following the death of husband, Lemuel. The injured Civil War soldier and former Baptist minister had only been in the position for six months. Kate was the mother of 10 children, with four left at home during her six years of service to the light.

- Karen McDonnell was the last female keeper at White River Light Station in Whitehall, coming in in 1983 and serving into the 2000s.

- Annie McGuire was appointed keeper of the Pentwater lighthouse from 1877 until 1885, following the death of her husband, Francis. Rumor has it she was removed from her post for “drunkenness and irregular habits.”

- Catherine McGuire was acting keeper at the Thunder Bay Lighthouse with her husband, Peter, in 1874 and 1875 at which time the “acting” was dropped and she was an official assistant. They transferred to Marquette in March 1882. Catherine was removed from her post in July 1891, at the request of her husband…although he served two more years until 1893.

- Sisters Effie & Mary McKinley assisted in tending the St. James Harbor Light on Beaver Island during their father Peter McKinley’s poor health and subsequent paralization. For nine years, the girls effectively ran the light until the VanRiper’s took over in 1869.

- Harry Miller was assistant keeper at the Grand Haven light from 1872 until 1875 under husband.

- William Monroe was keeper of the Muskegon lighthouse from 1862-1871 following death of husband.

- Alice Nolan assisted her husband, John, at the Gull Rock lighthouse from March 1892 until November 1903.

- Mrs. Charles O’Malley was head keeper for eight months between 1854 and 1855 at the Bois Blanc Island light. There is no record of Charles serving at this light.

- Pricilla Parker served for a few weeks in 1873 t the Grand Traverse Lighthouse in Northport. In a March 1873 letter that Keeper Henry Schetterly wrote to his son, he mentions the woman but does not describe his relationship with her. In the letter, he went on to say that she had “bound” out her oldest child but that he convinced her to not bound out the other she had. According to a letter to the Superintendent of Lights, Schetterly claimed she kept the lighthouse from September 11-30, 1873 inclusive and requested authority to pay her as a laborer. Keeper Schetterly died just a short time later, on October 21 of that year.

- Roswell Pendergast was first assistant under her husband at the Gull Island light, from 1872 until 1874.

- Peter Peterson was acting keeper of the Sant Point Lighthouse from April 30 to June 16, 1913 following death of husband.

- Sarah Robinson was the wife of William Robinson at White River Light Station in Whitehall, having moved to area in 1860s with seven of eventually 13 children (three of whom died in childhood). Bill was first keeper, serving from 1875 to1919 and Sarah assisted with duties until she passed away in 1891.

- Matilda Rumrill was acting first assistant keeper at Gull Island light in 1874 and 1875, under her husband, Pliny. The “acting” was dropped at that time, and she continued to serve until 1882. They stayed until 1883. Keepers of Gull Island were stationed on Michigan Island, and manned both.

- Lydia Smith was an assistant keeper at the Manitou Island in 1855 and 1856.

- Mary Snow was assistant keeper at Raspberry Island light from 1880 to 1882 under husband Seth, who kept the light until 1885.

- M. Stevens was acting first assistant t the Menagerie Island light from October 26, 1875 until November 18, 1876) under husband, William, before being promoted to actual assistant keeper until August 9, 1878.

- Mary L. Terry was appointed the first keeper of the Sand Point Lighthouse in Escanaba, when it was first opened in 1868. Her husband, John, was supposed to be the first keeper but he died before it was complete. Mary served 18 years before dying in a mysterious fire at the light in 1886.

- Mary Thomson, wife of keeper Thomas, served for three months as an acting keeper of the Eagle Harbor Range light following the departure of Mary Wheatley in 1905 (see below). Thomas then took over the position, until 1908.

- Anastasia “Eliza” Truckey was the acting keeper at the Marquette lighthouse between December 12, 1861 and October 26, 1865 while husband, Nelson, went to fight in the Civil War. A friend of the Native American’s in the area, Eliza was known as “Mother of the Light” and rumor has it that her mediation skills resulted in several “locals” being allowed to keep their scalps after disagreements with the Natives.

- Mary H. Vreeland was head keeper of the Gilbraltar light from 1876 until 1879 following death of husband, Michael. The station closed in 1879.

- Mary A. Wheatley was appointed keeper of the Eagle Harbor Range Light from 1898 until 1905, when she resigned. Her son, William, was keeper at Granite Island (1885-1893), with his father, James, shown as an assistant and later keeper. William drowned in a squall in 1898 on his way back to the island in a small sailboat to visit his father, who was keeper at the light until 1915. No explanation as to why Mary and James were tending different lights. Mary appears to have taken over following her son’s death.

For more, check out these books on female lighthouse keepers in Michigan:

Other Great Lakes lighthouse resources:

If you find items in this article which need correction, please email travel@promotemichigan.com.